RWE Source Selector Tool

Select Your Criteria

Recommendation

Registries vs. Claims Data Comparison

- Best for: Rare diseases, detailed clinical tracking

- Key strength: High clinical detail (87% lab value completeness)

- Limitation: Small population (1,000-50,000 patients)

- Cost: $1.2M - $2.5M to establish

- Best for: Large populations, common drugs

- Key strength: Massive scale (100M-300M patients)

- Limitation: Low clinical detail (52% lab value completeness)

- Cost: Minimal (uses existing systems)

When a new drug hits the market, the clinical trial data that got it approved is just the beginning. Real-world evidence (RWE) is what comes next - the ongoing, real-life look at how drugs behave outside the controlled environment of a trial. Two of the most powerful sources for this kind of evidence are registries and claims data. Together, they help regulators, doctors, and drug makers spot safety problems that clinical trials simply can’t catch.

What Is Real-World Evidence and Why Does It Matter?

Real-world evidence isn’t from labs or tightly monitored studies. It’s pulled from everyday healthcare settings: hospitals, pharmacies, insurance claims, and patient tracking systems. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) started formally using RWE for drug safety decisions around 2017, and since then, it’s played a role in approving 12 drugs or new uses - five of them based directly on claims or registry data.

Why does this matter? Clinical trials usually involve a few thousand patients over a couple of years. Real-world data can track hundreds of thousands - even millions - of people over decades. That’s how you find rare side effects, like a heart rhythm problem that only shows up in 1 in 10,000 users. Trials miss those. Registries and claims data don’t.

How Registries Work: Deep, Detailed, But Smaller

Disease registries are databases that collect detailed, structured information about patients with specific conditions. Think of them as long-term patient diaries, kept by doctors and researchers. A registry for cystic fibrosis, for example, tracks everything: lung function tests, which medications are used, hospital visits, and even how patients feel day to day.

These registries are gold for safety monitoring because they capture clinical details that claims data can’t. Lab results, imaging reports, genetic data - all of it gets recorded. According to a 2021 study, registries offer 37% more detail on long-term outcomes than claims data alone.

The FDA approved pembrolizumab’s expanded use in 2017 partly because of registry data from an expanded access program. The Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients helped confirm the safety of tacrolimus in 2021 by tracking thousands of transplant patients over time. The Cystic Fibrosis Foundation’s registry even found a safety signal for ivacaftor in patients with rare gene mutations - something the original trial didn’t catch because those mutations were too uncommon.

But there’s a catch. Registries are expensive and slow to build. Setting one up can cost $1.2 million to $2.5 million and take two years. Most have only a few thousand to 50,000 patients. And participation isn’t mandatory - only 60% to 80% of eligible patients join. That introduces selection bias. If sicker or more tech-savvy patients are more likely to sign up, the data might not reflect the full population.

Claims Data: The Power of Scale

Claims data is what insurance companies and government programs like Medicare collect every time someone visits a doctor, gets a prescription, or is admitted to the hospital. It includes diagnosis codes (ICD-10), procedure codes (CPT), drug codes (NDC), and billing information. It’s not clinical - it’s administrative. But it’s huge.

IBM MarketScan covers 200 million lives. Optum has 100 million. Truven Health has 150 million. Medicare claims alone go back 15+ years for each beneficiary. That’s more than enough to track long-term side effects like kidney damage or cancer risk after a drug has been on the market for a decade.

The FDA used Medicare claims data in 2015 to study entacapone, a Parkinson’s drug, and found no increased cardiovascular risk in 1.2 million patients. In 2014, they reviewed olmesartan (Benicar) in 850,000 diabetic patients to check for heart-related side effects. Both studies relied entirely on claims data.

Claims data is also how palbociclib got its expanded approval in 2019. The FDA looked at claims, electronic health records, and safety reports together to confirm the drug was safe for new patient groups.

But here’s the downside: claims data doesn’t tell you how a patient felt. It doesn’t include blood pressure readings, weight changes, or symptoms reported by the patient. Lab values are missing in 40-55% of records. Diagnosis codes can be wrong - up to 20% of the time, according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). And if a patient sees a specialist outside the network, that visit might not show up at all.

Comparing Registries and Claims Data Side by Side

| Feature | Registries | Claims Data |

|---|---|---|

| Population Size | 1,000 - 50,000 patients | 100 million - 300 million patients |

| Data Completeness (Lab Values) | 87% | 52% |

| Longitudinal Coverage | 5-15 years (on average) | 15+ years (Medicare) |

| Clinical Detail | High - includes imaging, symptoms, genetics | Low - only codes and billing info |

| Cost to Establish | $1.2M - $2.5M | Minimal (uses existing systems) |

| False Signal Rate | Low (due to rich context) | High - up to 22% require clinical review |

| Best For | Rare diseases, genetic conditions, long-term outcomes | Common drugs, large populations, rare adverse events |

The numbers tell a clear story: if you need depth, go with registries. If you need breadth, claims data wins. But neither is perfect alone.

Why Combining Them Works Best

Registries give you the clinical context. Claims data gives you the population scale. Together, they cancel out each other’s weaknesses.

The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) released new guidance in June 2023 saying exactly that: use both. When you combine them, false positive safety signals drop by 40%. That means fewer unnecessary drug warnings and fewer wasted investigations.

Take the FDA’s Sentinel Initiative. It’s not just one database. It connects 11 healthcare systems and 3 claims processors to monitor 300 million patient records. That’s the gold standard - using claims for volume and registries for detail when needed.

Even the European Medicines Agency (EMA) is moving this way. Its Darwin EU network, launched in 2021, now pulls data from 32 healthcare databases across 15 countries. It’s not just about one country - it’s about cross-border safety monitoring. By October 2023, it covered 120 million EU citizens.

Challenges and Pitfalls

It’s not all smooth sailing. Data standardization is the biggest headache. One hospital codes diabetes as E11. Another uses 250.9. Getting them to match takes 40-60% of a project’s time and budget.

Privacy laws like HIPAA in the U.S. and GDPR in Europe add layers of complexity. You can’t just grab patient records. Data must be de-identified, encrypted, and handled under strict protocols.

And then there’s bias. Claims data misses people without insurance. Registries miss people who don’t volunteer. Both can skew results. The FDA’s 2022 guidance specifically warns about “immortal time bias” - a statistical trap where patients are incorrectly labeled as safe because they survived long enough to be counted. Using the right methods can cut that bias by 35-50%.

Finally, sustainability. About 35% of academic registries shut down within five years. They run out of funding. Without ongoing support, valuable long-term data disappears.

The Future: AI, Wearables, and Standardization

Things are changing fast. In January 2024, the FDA released draft guidance requiring at least 80% data completeness for key variables in registry studies. That’s a big step toward quality control.

The FDA’s 2023-2027 RWE plan includes building five to seven new analytical standards for claims data by 2025. That means better tools to detect signals, filter noise, and avoid false alarms.

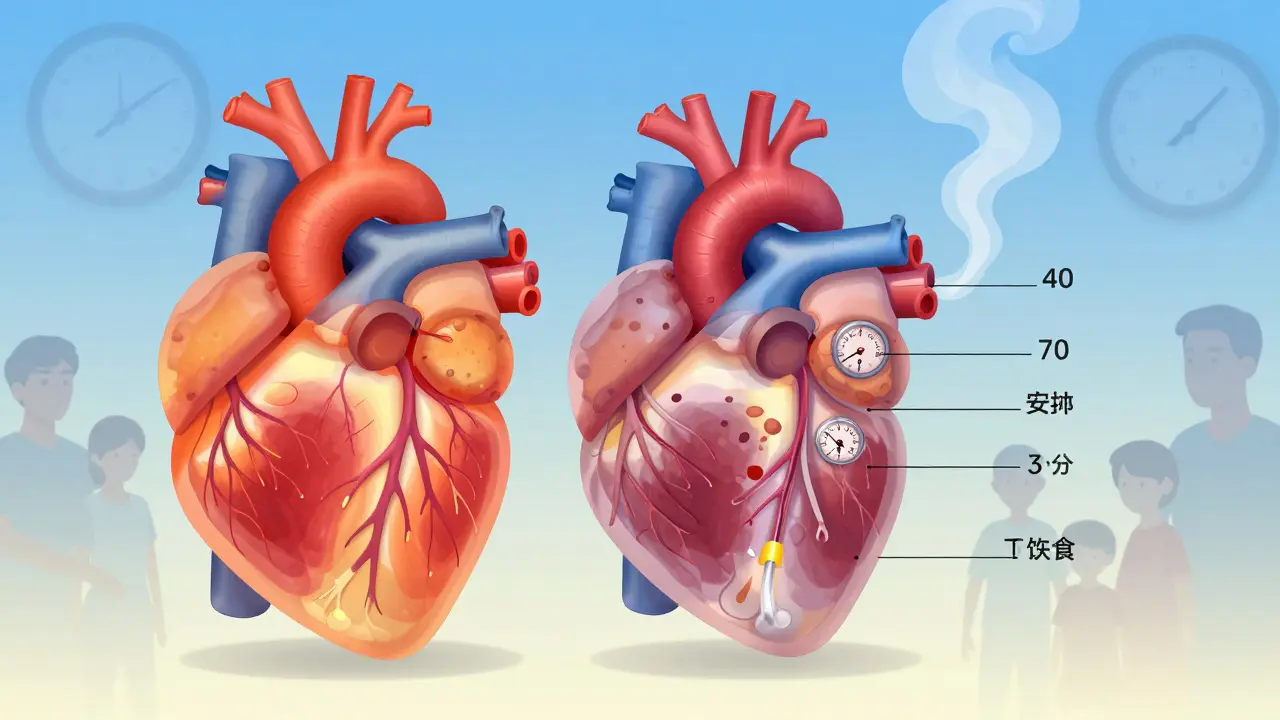

And now, some companies are adding wearables. Novartis started using smartwatches to track heart rate and activity in patients on Entresto - a heart failure drug. Combining that real-time data with claims records gave them a more complete picture of safety.

AI is also stepping in. A 2024 study in JAMA Network Open showed AI-powered signal detection cut false positives by 28%. It doesn’t replace humans - it helps them focus on the real red flags.

The FDA’s REAL program, launched in 2023, is trying to standardize registry data for 20 priority diseases by 2026. The first focus? Rare diseases. Why? Because traditional trials can’t recruit enough patients. Registries are the only way to monitor safety for these groups.

What This Means for Patients and Providers

For patients, this means drugs are being monitored more closely than ever. If a side effect emerges years after approval, regulators can act faster because they’re not waiting for a few hundred reports - they’re seeing patterns in millions of records.

For doctors, RWE helps answer real questions: Is this drug safe for my elderly patient with kidney disease? Does it interact with their other meds? The answers are no longer just based on trial results from healthy 30-year-olds.

And for the system as a whole, it’s a win. RWE is cheaper than running new trials. It’s faster than waiting for adverse events to pile up. And it’s more accurate than relying on voluntary reports.

The global market for RWE is projected to hit $10.7 billion by 2030. Pharmaceutical companies are now spending 8-12% of their pharmacovigilance budgets on it - up from just 3-5% in 2017. That’s not a fad. It’s the new normal.

What’s the difference between real-world data (RWD) and real-world evidence (RWE)?

Real-world data (RWD) is the raw information collected from everyday sources like electronic health records, insurance claims, and patient registries. Real-world evidence (RWE) is the clinical insight you get after analyzing that data. Think of RWD as the ingredients and RWE as the finished meal.

Can claims data prove that a drug causes a side effect?

Not alone. Claims data can show a pattern - like more heart attacks in patients taking Drug X. But it can’t prove cause and effect. That’s why regulators always look for supporting evidence: clinical reviews, lab data, or registry input. Claims data flags a possible problem; other data confirms it.

Why do registries cost so much to set up?

Because they require trained staff to collect, verify, and enter detailed clinical data - not just codes. You need doctors to input lab results, nurses to follow up with patients, IT systems to store imaging and genetic data, and quality controls to ensure accuracy. It’s labor-intensive and requires long-term funding.

Are registries only used for rare diseases?

No. While they’re especially valuable for rare diseases - where trials are too small - they’re also used for cancer, autoimmune diseases, and transplant patients. The key is when you need detailed, long-term clinical tracking, not just billing info.

How does the FDA use registry data in drug approvals?

The FDA uses registry data to support supplemental approvals - like expanding a drug’s use to new patient groups or confirming long-term safety. For example, registry data helped approve pembrolizumab for more cancer types and tacrolimus for new transplant patients. It doesn’t replace trials, but it adds critical real-world proof.

Is claims data reliable for tracking drug side effects in older adults?

Yes - especially because Medicare claims cover 15+ years of data for seniors. That’s longer than most clinical trials. But it’s only reliable if you account for comorbidities and drug interactions. Older patients often take multiple medications, and claims data can miss those unless carefully analyzed.

Can patients opt out of having their data used in registries or claims systems?

In claims data, patients usually can’t opt out - it’s part of billing. But in voluntary registries, participation is always optional. Patients must give informed consent before joining. Their data is anonymized, and they can leave at any time.

What’s the biggest limitation of using claims data for drug safety?

The biggest limitation is missing clinical context. Claims tell you a patient was diagnosed with diabetes and got a prescription - but not their blood sugar levels, diet, or symptoms. Without that, it’s hard to tell if a side effect is real or just a coincidence.