Military Tetanus Prophylaxis Calculator

This tool helps medics determine the appropriate tetanus prophylaxis based on wound type and vaccination status.

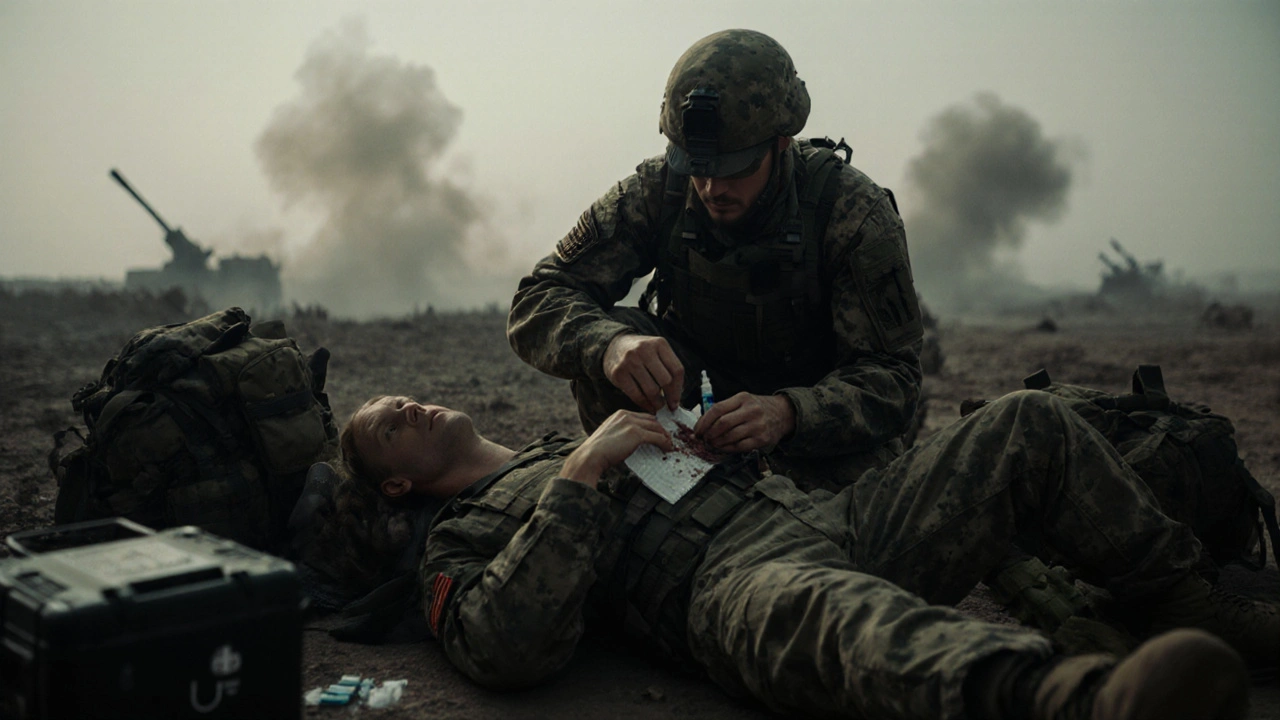

When a soldier suffers a deep cut in a dusty combat zone, Tetanus is a potentially fatal neurotoxic disease caused by the bacterium Clostridium tetani. The toxin locks muscles in a painful spasm, turning a simple wound into a life‑threatening emergency. In war zones where sanitation is scarce and evacuation can take hours, preventing and treating tetanus becomes a top priority for medics.

Why tetanus matters on the battlefield

Combat injuries are often contaminated with soil, rust, or debris-perfect breeding grounds for Clostridium tetani. Unlike civilian hospitals, forward operating bases lack sterile operating rooms, so a wound that would be quickly cleaned on the home front can become a ticking time bomb overseas. Mortality rates for untreated tetanus in conflict zones have been reported as high as 30%, compared with under 5% in modern civilian intensive care.

The bacterium behind the disease

Clostridium tetani is an obligate anaerobe that forms resilient spores capable of surviving harsh environments for decades. When a spore lands in a low‑oxygen wound, it germinates, multiplies, and releases tetanospasmin-the toxin that interferes with inhibitory neurotransmitters.

Prevention: vaccines and immunization policies

Modern armies rely on routine immunization to keep troops protected. The tetanus vaccine (often combined as Tdap or Td) contains inactivated tetanus toxoid that primes the immune system without causing disease. Most militaries require a primary series before deployment and a booster every 10 years, aligning with World Health Organization recommendations.

- Initial series: three doses at 0, 1, and 6 months.

- Booster: every 10years or after a high‑risk injury.

- Special groups (e.g., new recruits) may receive an accelerated schedule.

Treating injuries: debridement, antibiotics, and immune globulin

When a wound is contaminated, the first step is aggressive wound debridement-removing all dead tissue and foreign material. This reduces the oxygen‑free environment that spores love.

Antibiotics such as penicillin or metronidazole are given to suppress bacterial growth, but they do not neutralize toxin already produced. That’s where tetanus immune globulin (TIG) comes in: a passive antibody that binds free toxin and prevents it from reaching nerves.

| Option | Mechanism | Typical Dose | When to Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tetanus Vaccine | Active immunization - stimulates antibody production | 0.5mL intramuscular | Patient not up‑to‑date on immunization |

| TIG | Passive immunity - neutralizes circulating toxin | 250-500IU intramuscular | Severe wounds, unknown vaccination status, or delayed presentation |

| Antibiotics | Inhibits bacterial growth | Penicillin G 2millionU IV q6h | All contaminated wounds (adjunct to other measures) |

Field protocols: NATO and WHO guidelines

Both NATO medical doctrine and WHO’s “Combat Trauma Care” handbook recommend a standardized decision tree. After initial assessment, medics check the soldier’s immunization record. If the record is missing or the last dose was over 10years ago, they administer vaccine plus TIG for deep puncture wounds. For minor abrasions, a booster alone suffices.

These protocols are distilled into pocket cards that list wound types, required prophylaxis, and dosage charts-ensuring rapid, uniform care even when communications are down.

Logistics: vaccine storage and cold chain in conflict zones

Keeping the tetanus vaccine viable in desert heat or jungle humidity is a logistical nightmare. Modern militaries use portable solar‑powered refrigerators that maintain 2-8°C. Temperature‑loggers are attached to each vaccine vial, and any breach triggers a discard and replacement from the central medical depot.

During the 2022‑2023 Eastern European conflict, a field hospital reported a 3% wastage rate due to cold‑chain failures-a figure that dropped to under 0.5% after adopting passive cooling packs engineered for rugged use.

Lessons learned from recent conflicts

Case studies from Afghanistan, Iraq, and the recent Sahel operations highlight three recurring themes:

- Early debridement saves lives. Delays beyond 6hours doubled tetanus incidence.

- Vaccination status must be recorded electronically; paper logs are often lost during relocations.

- Rapid administration of TIG within the first 24hours dramatically reduces severe spasms.

Training drills now incorporate simulated tetanus scenarios, forcing medics to decide between vaccine, TIG, and antibiotics in under two minutes.

Future directions: rapid diagnostics and new vaccines

Scientists are developing point‑of‑care assays that detect tetanospasmin in wound exudate within minutes. If validated, these tests could spare soldiers from unnecessary TIG when toxin levels are low, conserving limited supplies.

On the vaccine front, a recombinant subunit candidate promises a longer‑lasting immune response with a single dose-potentially cutting booster schedules in half.

By weaving together prevention, swift treatment, and robust logistics, armed forces can keep tetanus from turning a battlefield injury into a fatal event.

Frequently Asked Questions

How quickly must tetanus prophylaxis be given after a combat injury?

Ideally within the first 24hours. The sooner TIG and vaccine are administered, the lower the risk of severe toxin effects.

What is the difference between tetanus vaccine and tetanus immune globulin?

The vaccine stimulates the body to produce its own antibodies (active immunity) and offers long‑term protection. TIG provides immediate, short‑term neutralization of toxin already in the bloodstream (passive immunity).

Can a soldier rely on antibiotics alone to prevent tetanus?

No. Antibiotics stop bacterial growth but do not inactivate the toxin already released. They must be combined with vaccine or TIG for effective prophylaxis.

What are the storage requirements for tetanus vaccine in field hospitals?

Vaccines must be kept at 2-8°C. Portable solar‑powered refrigerators or insulated cold packs with temperature loggers are the standard solutions for remote deployments.

How often should military personnel receive tetanus boosters?

A booster is recommended every ten years, or sooner if a high‑risk wound occurs and the last dose was more than five years prior.

yash Soni

September 30, 2025 AT 18:46Oh great, another lecture on battlefield tetanus. Because we definitely needed more paperwork on wound dressing. Sure, let’s all memorize tables while soldiers bleed.

Emily Jozefowicz

October 9, 2025 AT 15:46I see where you're coming from, but the real issue is ensuring medics have the right tools, not debating policy. The color‑coded pocket cards are a nice touch, yet they’re only as good as the training behind them.

Franklin Romanowski

October 18, 2025 AT 12:46When we think about tetanus on the front lines, it’s not just a medical problem-it’s a moral one. Every wounded soldier carries the weight of a nation’s promise to protect them. The protocols here remind us that vigilance is a collective responsibility.

Brett Coombs

October 27, 2025 AT 08:46Sure, NATO says “follow the chart,” but who’s to say the chart wasn’t designed by people who never saw a muddy trench? I’ve heard whispers that supply chains are deliberately sabotaged to keep us dependent on foreign manufacturers.

John Hoffmann

November 5, 2025 AT 05:46The article provides a thorough overview of tetanus prophylaxis, yet several points merit clarification. First, the distinction between active and passive immunity should be emphasized, as many medics conflate the two. Second, the recommended timing of tetanus immune globulin (TIG) administration is critical; it must be given within the first 24 hours to neutralize circulating toxin effectively.

Third, the dosage guidelines for TIG (250‑500 IU intramuscular) are based on body weight and wound severity, but field conditions often preclude precise calculations, so a standard dose is advisable.

Fourth, cold‑chain logistics are not merely a technical footnote; vaccine potency drops precipitously outside the 2‑8 °C range, leading to possible primary vaccine failure.

Fifth, debridement should be performed as soon as possible-ideally within six hours-to reduce anaerobic conditions that favor Clostridium tetani.

Sixth, antibiotic therapy (penicillin G or metronidazole) is adjunctive and does not replace the need for TIG when toxin is present.

Seventh, the article mentions “accelerated schedule” for new recruits but does not specify the exact intervals; a common protocol is 0, 1, and 2 months with a booster at 12 months.

Eighth, documentation of vaccination status must be electronic; paper logs are prone to loss during relocations, as highlighted in recent conflict zones.

Ninth, the pocket cards referenced are valuable, but they must be kept up to date with the latest WHO guidelines, which occasionally revise dosage recommendations.

Tenth, training drills that simulate tetanus scenarios are essential for reducing decision‑making time; the article correctly notes the two‑minute target.

Eleventh, point‑of‑care diagnostics for tetanospasmin are promising, yet current field validation is limited, so clinicians should continue to rely on clinical judgment.

Twelfth, the logistical note about solar‑powered refrigerators is accurate, but backup generators should also be considered for redundancy.

Thirteenth, vaccine wastage rates dropping from 3 % to 0.5 % demonstrate the impact of proper cold‑chain management and should be a benchmark for all deployments.

Fourteenth, the article could benefit from a flowchart illustrating decision points for vaccine versus TIG administration.

Fifteenth, overall the piece is informative, but the inclusion of more real‑world case studies would enhance its practical utility.

Mustapha Mustapha

November 14, 2025 AT 02:46Solid rundown of the protocols. I especially appreciate the note on portable solar‑powered fridges-those have saved a lot of doses in the field. Staying chill and following the steps will keep our troops safer.

Ben Muncie

November 22, 2025 AT 23:46If you think the vaccine is optional, think again.

lee charlie

December 1, 2025 AT 20:46Every soldier deserves quick care, and the protocols described are a solid step toward that goal. With the right training, medics can act within the crucial first hours.

Greg DiMedio

December 10, 2025 AT 17:46Wow, another endless read about tetanus, probably could've been a tweet. Too many tables, not enough punch.

Badal Patel

December 19, 2025 AT 14:46Whilst the author hath expounded upon prophylaxis, one must inquire: hath the field truly embraced these stratagems, or doth bureaucracy impede? The dramatics of policy often eclipse the stark realities of mud‑soaked wounds.

KIRAN nadarla

December 28, 2025 AT 11:46Your article is informative, but the misuse of commas and inconsistent capitalization detract from its credibility. For example, "tetanus immune globulin (TIG)" should not be preceded by a comma when it follows a clause. Additionally, bullet points need parallel structure: "Initial series" versus "Booster" are mismatched. Proper grammar enhances authority, especially in medical guidelines.

Kara Guilbert

January 6, 2026 AT 08:46i think the author is being to moralistic about vaccines. its not about being purist, its about real life.

Sonia Michelle

January 15, 2026 AT 05:46From an ethical standpoint, the duty to provide rapid tetanus care aligns with the principle of beneficence. If we neglect these protocols, we compromise not only health outcomes but also the trust soldiers place in their support systems. Let’s keep the conversation grounded in compassion.

Neil Collette

January 24, 2026 AT 02:46Listen, the whole point is you’re missing the forest for the trees-field medics don’t have time to debate semantics, they need clear, actionable steps. The article’s detail is nice, but simplify the decision tree for real‑world use.

James Lee

February 1, 2026 AT 23:46Honestly, this write‑up feels like a college essay trying too hard to sound smart. The jargon is over‑the‑top and the misspelling of "vaccination" hurts credibility. Keep it simple, bro.

Dennis Scholing

February 10, 2026 AT 20:46Dear colleague, while your concerns about style are noted, it would be constructive to propose concrete revisions rather than mere criticism. A collaborative edit could elevate the piece for all readers.

joshua Dangerfield

February 19, 2026 AT 17:46Interesting points all around, especially the cold‑chain solutions. Glad to see practical tech being discussed.