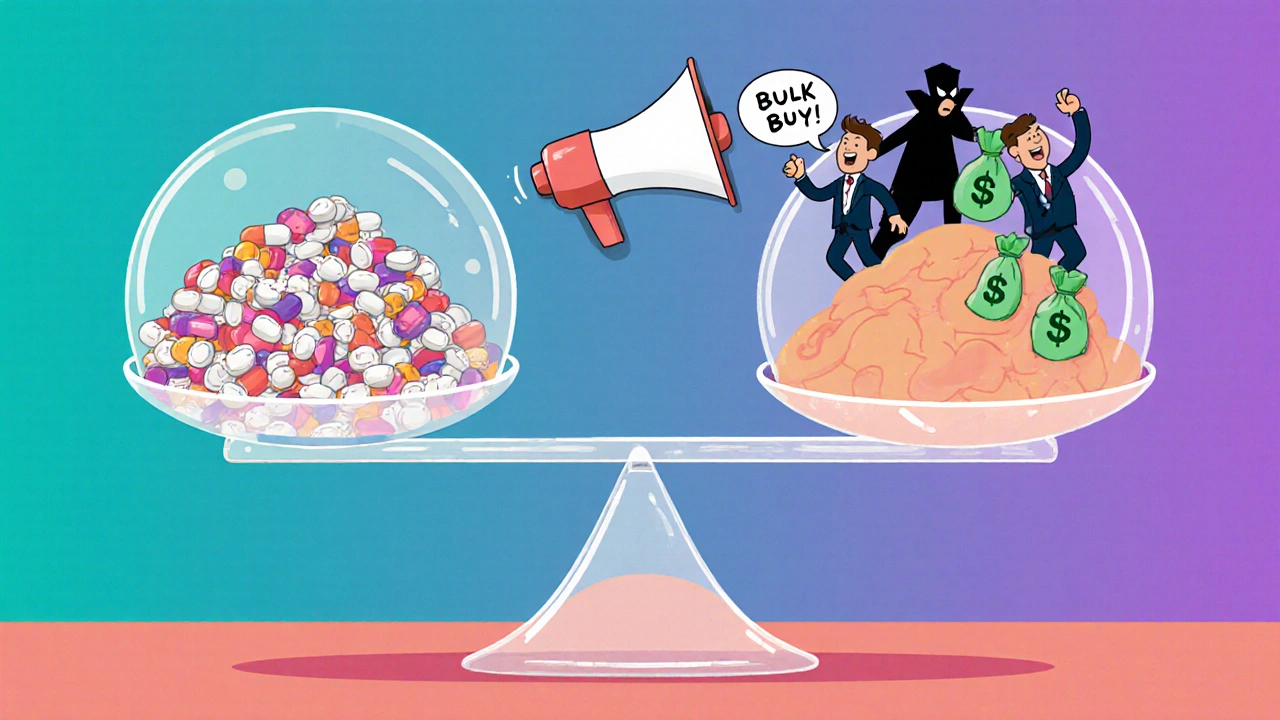

Most people assume their insurance covers generics at a low cost-until they see the bill. A $10 copay for a blood pressure pill? That’s the myth. In reality, many insurers are paying far more than they should for generic drugs, and the difference often ends up in the pockets of middlemen, not the patient. The truth? Insurers save millions by using bulk buying and tendering-but only if they know how to do it right.

What Bulk Buying and Tendering Actually Means

Bulk buying isn’t just ordering more pills at once. It’s a strategic negotiation where insurers, pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), and large health systems pool their purchasing power to force generic drug manufacturers into competitive bidding. Think of it like a wholesale warehouse for medicine-except instead of toilet paper, they’re buying thousands of doses of metformin, lisinopril, or atorvastatin.

Tendering is the process behind it. Insurers issue a request for bids (RFB) for a specific generic drug-say, a 30-day supply of simvastatin. Three manufacturers respond with price offers. The insurer picks the lowest, but only if the manufacturer agrees to supply a minimum volume over 1-3 years. That guarantee gives the manufacturer stability. In return, the insurer gets a price 70-90% lower than retail.

This isn’t theory. According to the Association for Accessible Medicines, generics made up 90.7% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S. in 2023-but only 17.3% of total drug spending. That’s the power of volume.

How Much Do Insurers Really Save?

The savings are staggering. A single first-time generic drug approval can save over $1 billion in its first year, according to the FDA. For example, when the generic version of Vimpat (lacosamide) hit the market, it slashed prices from $1,200 per month to under $100. That’s an 92% drop.

But the real wins come from consistent, ongoing tendering. A 2022 JAMA Network Open study found that insurers who actively managed their generic formularies saved up to 80% compared to those who didn’t. One health plan reduced its spending on a common antibiotic from $45 to $6 per prescription just by switching to a lower-cost manufacturer.

Even small changes add up. If an insurer covers 10,000 members taking a $30 generic drug and switches to a $7 alternative, they save $230,000 per month. That’s $2.76 million a year-just from one drug.

The Problem: PBMs and Hidden Pricing

Here’s where it gets messy. Most insurers don’t buy generics directly. They rely on pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) like OptumRx, Caremark, or Express Scripts. These companies act as middlemen-and they’re not always working for you.

PBMs use a practice called “spread pricing.” They tell the insurer they paid $10 for a drug, but they actually paid $4 to the pharmacy. The $6 difference? That’s their profit. And guess what? They often choose higher-priced generics because they make more money on the spread.

That’s why you see $25 copays for generics that cost $3 at Costco. Your insurer thinks they’re saving money. But they’re being played.

A 2023 NIH study showed that direct-to-consumer pharmacies like Mark Cuban’s Cost Plus Drug Company offered median savings of 76% on expensive generics compared to retail. One patient paid $87 through insurance for a generic pill. Paid $4.99 cash at Cost Plus. Same drug. Same pharmacy chain. Just no PBM in between.

How Insurers Fix This

The smart ones cut out the middleman. They either:

- Use transparent PBM contracts that require full price disclosure (like California’s SB 17 law), or

- Build their own bulk purchasing networks with direct manufacturer contracts.

Some employers now bypass PBMs entirely. They partner with pharmacy networks like Navitus Health Solutions, which reported 22% lower generic costs for clients in 2023. Others use tools like GoodRx or SingleCare to compare cash prices-then pay cash instead of using insurance.

But the most effective strategy? Regular formulary reviews. High-cost generics often come from manufacturers with little competition. If only one company makes your insurer’s preferred version of a drug, they can charge more. The fix? Swap it out for a similar drug made by three or four manufacturers. That triggers competition-and lower prices.

Real-World Examples

Consider this real case from a mid-sized employer in Texas. They noticed their generic diabetes drug, glipizide, was costing $18 per prescription. A quick review showed another version, made by a different manufacturer, was available for $3.50. They switched. The plan saved $14,000 in one month.

Another insurer in Florida analyzed their top 20 most expensive generics. They found five drugs with only one manufacturer. They opened bids. Three of those five dropped 80% in price within 90 days.

Even Medicare Part D plans are catching on. Since 2022, CMS has required more pricing transparency. Some plans now show members the cash price versus the insurance price-so they can choose.

Why Some Insurers Still Lose Money

Not every insurer is winning. Many still rely on outdated PBM contracts. Some don’t audit their formularies more than once a year. Others fear backlash from pharmacies or patients who are used to certain brands-even if they’re overpriced.

And then there’s the shortage risk. When prices get pushed too low, manufacturers quit. In 2020, albuterol inhalers disappeared because no one could make them profitably at $1.50 per unit. Hospitals reported 87% shortages. That’s what happens when tendering goes too far.

The key is balance. Insurers need to push for low prices-but not so low that supply vanishes. The sweet spot? A price that’s 70-80% below brand-name cost, with at least two manufacturers ready to supply.

What Patients Can Do

You don’t need to be an insurer to benefit. If you’re paying high copays for generics:

- Check GoodRx or SingleCare before you pay. Often, the cash price is lower than your copay.

- Ask your pharmacist: “Is there a cheaper generic version?”

- Call your insurer and ask: “Why is this generic so expensive? Are there alternatives?”

- If you’re on Medicare, compare your plan’s formulary. Some plans have better generic pricing than others.

One GoodRx user reported saving $32 a month on three generics by ignoring insurance entirely. That’s $384 a year-just by asking the right questions.

The Future: Transparency and Control

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 didn’t fix the PBM problem-but it opened the door. New rules require Medicare Part D plans to disclose PBM pricing by 2025. More states are following California’s lead with price transparency laws.

Insurers who embrace direct contracting, regular formulary audits, and manufacturer competition will keep saving. Those who don’t? They’ll keep overpaying-and passing the cost to members.

The bottom line? Generic drugs aren’t expensive because they’re costly to make. They’re expensive because the system is broken. Fix the procurement, and you fix the price.

How do insurers save money on generic drugs?

Insurers save by using bulk buying and tendering-pooling large volumes of generic drug orders to force manufacturers into competitive bidding. This drives prices down 70-90% compared to retail. They also swap out high-cost generics with cheaper, clinically equivalent alternatives and audit their formularies regularly to spot overpriced drugs.

What’s the difference between a PBM and bulk buying?

A pharmacy benefit manager (PBM) acts as a middleman between insurers and pharmacies, often using hidden pricing like “spread pricing” to make profits. Bulk buying cuts out the middleman-insurers negotiate directly with manufacturers, paying transparent, low prices based on volume. This eliminates hidden fees and ensures savings go to the plan, not the PBM.

Why are some generic drugs so expensive even though they’re “generic”?

Some generics cost more because they’re made by only one or two manufacturers, leaving no competition. Others are priced high because PBMs get paid more when the drug costs more (through spread pricing). The drug itself isn’t expensive to produce-it’s the system that inflates the price.

Can patients save money by avoiding insurance for generics?

Yes. Many patients pay less out-of-pocket using cash prices from GoodRx, Cost Plus Drug Company, or Costco than they do with insurance. In 2023, 97% of cash payments for prescriptions were for generics, showing patients already know insurance isn’t always the best deal.

What’s the biggest mistake insurers make with generics?

The biggest mistake is not reviewing their formulary regularly. Many insurers use the same generic drugs year after year-even when cheaper, equally effective alternatives exist. Without quarterly audits, they’re leaving money on the table and overpaying by thousands per drug.

Insurers who treat generics like a commodity-instead of a strategic lever-are paying too much. Those who treat them like a negotiation opportunity? They’re saving millions. And patients? They’re the ones who benefit the most.

Katelyn Sykes

November 18, 2025 AT 10:32Sarah Frey

November 18, 2025 AT 12:46It's not about distrust in the system-it's about demanding accountability. And honestly, if we can negotiate bulk rates for toilet paper, why not for life-saving medication?

Gabe Solack

November 19, 2025 AT 02:27Yash Nair

November 20, 2025 AT 12:50Girish Pai

November 21, 2025 AT 23:15Kristi Joy

November 22, 2025 AT 00:31And if you're an insurer? Do better. Your members are counting on you.

Hal Nicholas

November 23, 2025 AT 21:06Louie Amour

November 25, 2025 AT 02:06Stop being a pawn. Pay cash. Use Cost Plus. Demand transparency. Or keep being a sucker.

Kristina Williams

November 26, 2025 AT 09:27Shilpi Tiwari

November 26, 2025 AT 20:31Christine Eslinger

November 28, 2025 AT 14:20Patients don't need a revolution. They just need to know they have choices. And if they choose to use them? The system has to change. It already is. Slowly. But it is.

So keep asking. Keep checking. Keep pushing. You're not just saving money-you're changing the game.

Denny Sucipto

November 30, 2025 AT 06:07And now I learn that the reason they cost so much is because some guy in a suit is pocketing the difference between what the pharmacy charges and what the insurer thinks they paid?

Man. I feel like I just got scammed by a magic trick. And the worst part? I paid for the ticket.

Time to start paying cash. My pharmacist doesn't even blink when I hand over $5. And my bank account? It's doing a happy dance.