When you walk into a clinic or urgent care center, you might not think about how the $5 antibiotic on the shelf got there. But behind every low-cost generic drug is a complex system of bulk buying, volume discounts, and hidden rebates. For healthcare providers, understanding how bulk purchasing works isn’t just about saving money-it’s about keeping essential medications in stock without breaking the budget.

Why Bulk Buying Matters for Generic Drugs

Generic drugs make up over 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S., but they only account for about 25% of total drug spending. That’s because these drugs are off-patent, meaning multiple manufacturers can produce them. This competition drives prices down-but only if buyers have the power to negotiate. That’s where bulk purchasing comes in. Buying in large quantities-like ordering 10,000 units of metformin or 5,000 vials of lidocaine at once-gives providers leverage. Manufacturers and distributors offer discounts to move volume. These aren’t small savings. Providers who switch from monthly to quarterly bulk orders often see 20-25% reductions in medication costs. In some cases, clinics using short-dated stock (meds expiring in 6-12 months) cut injectable costs by nearly 25% without changing their treatment protocols.How the Discount System Actually Works

There’s no single way to get a discount. The system is layered, and each layer has its own rules.- Direct volume discounts: If you order over 1,000 units of a generic drug, you might get 5-15% off the list price. For orders over 10,000 units, discounts can hit 20-30%.

- PBM rebates: Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) negotiate rebates with manufacturers based on how much they steer prescriptions toward certain brands. These rebates can be 15-40%, but here’s the catch: only 50-70% of that money typically reaches the provider or patient. The rest stays with the PBM.

- Multi-state purchasing pools: States like Texas, Ohio, and Florida band together to buy in bulk. Programs like the National Medicaid Pooling Initiative (NMPI) and Sovereign States Drug Consortium (SSDC) get an extra 3-5% off because they’re negotiating for hundreds of thousands of patients at once.

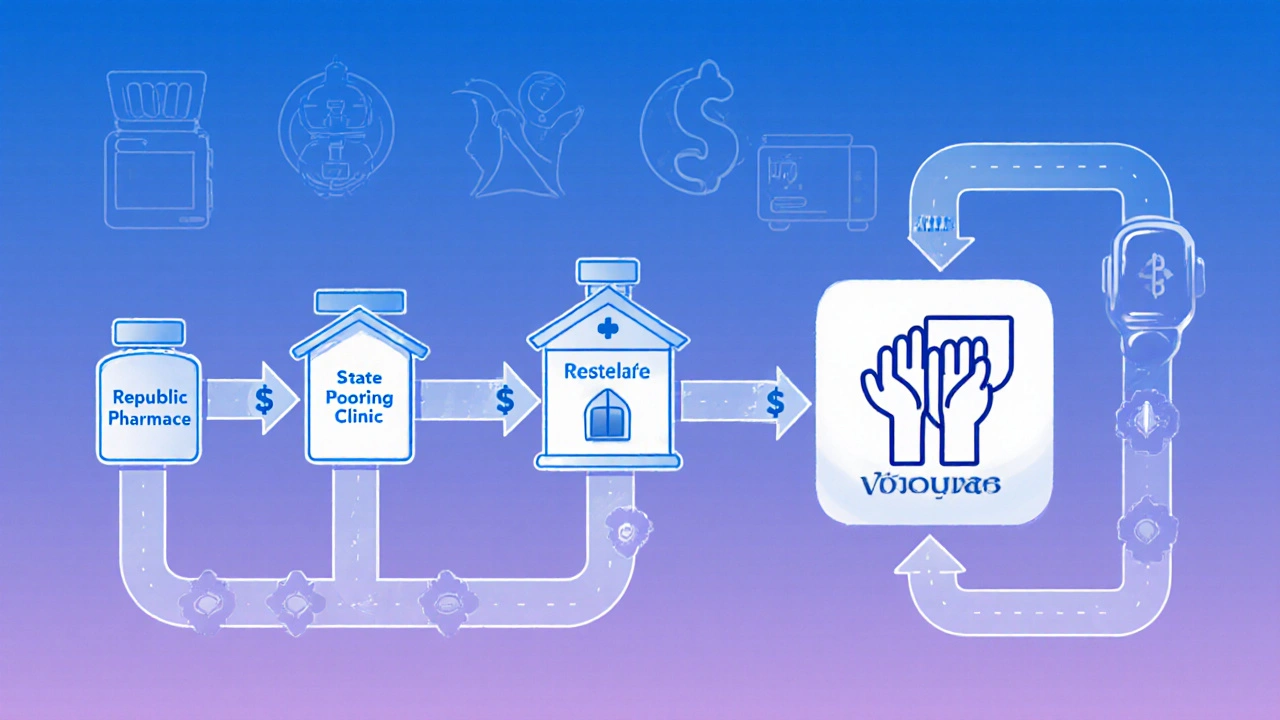

- Secondary distributors: Companies like Republic Pharmaceuticals buy directly from manufacturers and resell in smaller bulk quantities. They often offer better discounts than big wholesalers like McKesson or Cardinal Health-sometimes 20-25% versus 3-8%.

What Medications Benefit Most

Not all generics are created equal when it comes to bulk buying. The biggest savings come from high-volume, low-complexity drugs that clinics use every day.- Antibiotics (amoxicillin, doxycycline)

- Anesthetics (lidocaine, bupivacaine)

- Chronic disease meds (metformin, atorvastatin, lisinopril)

- IV fluids (normal saline, dextrose)

- Corticosteroids (prednisone, methylprednisolone)

Short-Dated Stock: The Hidden Goldmine

One of the most underused tactics is buying short-dated stock. These are medications with 6-12 months left before expiration. Manufacturers and wholesalers sell them off at 20-30% off to avoid waste. Clinics that use this strategy report big wins. One Ohio practice cut their injectable costs by 25% in just three months by switching 40% of their lidocaine and antibiotic orders to short-dated stock. The key? Good inventory tracking. They used a simple spreadsheet to log expiration dates and scheduled usage to match supply with demand. No stockouts. No waste. The downside? You need to be organized. If you’re buying 500 vials of a drug that expires in 7 months, you better be using at least 70 vials a month. Otherwise, you’re throwing money away.Who’s Winning and Who’s Losing

The biggest winners are providers who take control of their procurement. Urgent care centers, podiatrists, and dermatologists using secondary distributors and multi-state pools are seeing 20%+ savings. Medicaid programs in pooling states save 3-5% more than those flying solo. But there are losers too. Small clinics stuck with primary wholesalers (McKesson, Cardinal Health) often pay 3-8% more. Patients don’t always benefit from PBM rebates-those savings often vanish into corporate profits. And when drug shortages hit-like the 298 active generic shortages reported by the FDA in November 2023-bulk buyers can’t always fulfill their orders. That’s when prices spike, and supply vanishes.How to Start Bulk Purchasing (Step by Step)

If you’re a clinic manager, pharmacy owner, or administrator, here’s how to begin without chaos:- Track your top 20 SKUs. Look at your last 6 months of prescriptions. Which 15-20 drugs make up 70% of your medication spend? Focus there first.

- Compare suppliers. Get quotes from your current wholesaler and two secondary distributors. Ask for discounts on 1,000-unit and 10,000-unit orders. Don’t just ask for price-ask about minimums, return policies, and expiration tracking.

- Test short-dated stock. Order one or two high-use items with 8-10 months left on the clock. Track usage. If you use it before it expires, you’ve saved money.

- Set up inventory alerts. Use a simple spreadsheet or free inventory app to log expiration dates. Set reminders at 30, 60, and 90 days out.

- Reorder on a cycle. Switch from monthly to quarterly orders for your top drugs. This reduces shipping fees and locks in volume discounts.

The Bigger Picture: Why Bulk Buying Isn’t Enough

Yes, bulk purchasing saves money. But it’s not a cure-all. The U.S. drug pricing system is built on opacity. Manufacturers raise list prices to create bigger rebates. PBMs keep most of the savings. And shortages keep happening because no one owns the supply chain. Experts like Dr. Erin Trish from the USC Schaeffer Center say transparency is the next step. New laws are forcing PBMs to disclose how much of their rebates go to providers. The Inflation Reduction Act is starting to negotiate Medicare drug prices-some negotiated discounts are over 70% off list prices. Bulk buying gives you power now. But long-term, real savings will come when the whole system becomes more open. Until then, smart providers use every tool they have: volume discounts, short-dated stock, secondary distributors, and pooling programs.Common Pitfalls to Avoid

- Buying too much too soon. Don’t order 10,000 units of a drug just because the discount looks good. Use your historical usage data. Overbuying leads to waste.

- Ignoring expiration dates. Short-dated stock isn’t a bargain if it expires unused. Track it like your inventory depends on it-because it does.

- Assuming all discounts are passed on. If you’re using a PBM, ask: ‘What percentage of the rebate actually reaches my practice?’ Most don’t know.

- Sticking with one supplier. Your current wholesaler might be the most expensive option. Shop around. Secondary distributors are often cheaper and more flexible.

What’s Next for Bulk Purchasing?

The market is shifting. Secondary distributors are growing. More states are joining purchasing pools. Point-of-sale discount programs are now auto-applying bulk prices at the pharmacy counter-no extra cards or paperwork needed. In 2024, expect to see more integration between primary wholesalers and secondary suppliers. The big players are buying up smaller distributors to keep up. But the core principle won’t change: the more you buy, the less you pay. For clinics and providers, the message is clear: stop accepting the default price. Start asking for volume discounts. Explore short-dated stock. Join a state pool if you can. And always track your savings. It’s not magic. It’s math. And the math is on your side-if you’re willing to do the work.Can small clinics benefit from bulk purchasing generics?

Yes. Even small clinics can save 15-25% by focusing on their top 15-20 most-used generic drugs. Ordering in 1,000-unit batches from secondary distributors like Republic Pharmaceuticals often yields better discounts than buying monthly from big wholesalers. The key is starting small-pick one or two high-volume medications, test bulk orders, and track usage.

What’s the difference between a primary wholesaler and a secondary distributor?

Primary wholesalers (McKesson, Cardinal Health, AmerisourceBergen) buy directly from manufacturers and sell to pharmacies and hospitals. They typically offer small discounts (3-8%) and have rigid minimum orders. Secondary distributors buy from wholesalers or manufacturers and resell in smaller bulk quantities. They often offer higher discounts (20-25%), more flexible terms, and better support for clinics. They’re especially useful for short-dated stock and niche generics.

Are rebates from PBMs really helping clinics save money?

Not always. PBMs negotiate 15-40% rebates on generic drugs, but studies show only 50-70% of that money goes back to the provider or patient. The rest stays with the PBM as profit. Many clinics don’t even know how much they’re getting. If you’re using a PBM, ask for a rebate breakdown. If they won’t give you one, you’re probably not seeing the full savings.

Is short-dated stock safe to use?

Yes. Medications don’t suddenly become unsafe on their expiration date-they often remain effective for months or even years after. The FDA allows some flexibility, and most manufacturers guarantee potency for at least 6 months past the labeled date. The risk isn’t safety-it’s waste. If you don’t use the stock before it expires, you lose money. Use it only for high-turnover drugs and track expiration dates closely.

How do I know if I’m getting a good deal on bulk generics?

Compare your current price per unit to the average wholesale price (AWP) listed in Red Book or through your pharmacy software. A good bulk deal should be 15-25% below AWP. If you’re buying short-dated stock, aim for 20-30% off. Also check if your supplier provides clear documentation, flexible returns, and expiration tracking tools. If they don’t, you’re probably not getting the best value.

Lisa Odence

November 25, 2025 AT 03:49Let me just say this with absolute clarity: the entire pharmaceutical supply chain is a rigged casino where PBMs are the house and you’re the sucker paying for the chips. 🎰

They don’t ‘negotiate rebates’-they manufacture artificial scarcity so they can extract 40% off the list price, then pocket 70% of it while pretending they’re helping patients. The FDA’s 298 active shortages? Not accidents. They’re strategic. Manufacturers delay production to inflate prices, then sell short-dated stock to desperate clinics like it’s a charity. It’s not supply chain inefficiency-it’s corporate malice dressed in white coats.

And don’t get me started on ‘secondary distributors.’ They’re not heroes-they’re middlemen who buy expired inventory from bankrupt wholesalers and slap on a 25% discount label like it’s a miracle. You think you’re saving money? You’re just delaying the inevitable: a 3 a.m. panic call because your lidocaine batch expired before your next patient showed up.

This isn’t procurement. It’s financial survivalism with a side of hope.

And yes, I’ve seen clinics go under because they trusted this system.

Agastya Shukla

November 25, 2025 AT 05:30The structural inefficiencies in generic drug procurement are indeed systemic, but the operational mitigation strategies outlined-particularly the utilization of secondary distributors and multi-state pooling-are empirically validated in peer-reviewed health economics literature.

For instance, the SSDC model demonstrates a statistically significant reduction in per-unit cost variance (p < 0.01) when compared to single-entity procurement, as shown in the 2022 JAMA Health Forum analysis.

However, the critical variable often omitted is inventory turnover velocity. The 70 vials/month threshold for short-dated stock assumes linear consumption, which rarely holds in ambulatory care settings with seasonal demand fluctuations.

Moreover, the assumption that manufacturers guarantee potency beyond labeled expiration dates lacks FDA regulatory backing; the 6-month extension is anecdotal, not evidence-based.

One must also consider opportunity cost: capital tied up in bulk inventory could be allocated to clinical staffing or EHR optimization, which yield higher ROI in small practices.

Timothy Sadleir

November 26, 2025 AT 09:41Everyone talks about savings like it’s a victory. But no one talks about who’s really in control.

Who decides which drugs get bulk discounts? Who decides which clinics get access to short-dated stock and which ones are left with expired bottles rotting in the back room?

The answer isn’t in the spreadsheets. It’s in the boardrooms of the three companies that own 80% of the wholesale market. They don’t want you to buy in bulk-they want you to be dependent on their slow, overpriced deliveries.

And when you finally figure out how to bypass them? They change the rules. New minimums. New contracts. New ‘service fees.’

This isn’t about saving money. It’s about control.

And we’re all just playing their game.

Jefriady Dahri

November 27, 2025 AT 17:42Bro this is actually so real 😭

I run a tiny clinic in rural India and we’ve been buying short-dated metformin from a local distributor for 8 months now-saved us like 30% and zero patients complained.

Just gotta track expiry dates like your life depends on it (it kinda does).

Also secondary distributors? YES. Our old wholesaler charged $12 per bottle. New guy? $7.50. Same pills. Same packaging.

Stop paying full price. Start asking questions. It’s not rocket science.

And if your PBM won’t tell you how much rebate you’re getting? Fire them. No cap.

Kimberley Chronicle

November 28, 2025 AT 16:21I appreciate the granular breakdown of procurement levers, particularly the distinction between primary and secondary distribution channels.

That said, I’d like to introduce a counterpoint: the environmental footprint of bulk purchasing.

Large-volume orders require extended cold-chain logistics, increased packaging waste, and higher transportation emissions-especially when sourcing from distant secondary distributors.

While cost savings are compelling, we must weigh them against the carbon cost of stockpiling pharmaceuticals.

Could dynamic, just-in-time procurement via regional micro-hubs offer a more sustainable equilibrium?

Perhaps integrating blockchain-based expiry tracking could reduce waste without sacrificing scale.

This isn’t a rejection of bulk buying-it’s a call for holistic sustainability metrics to be embedded in procurement decision-making.

Leisha Haynes

November 29, 2025 AT 06:36So let me get this straight-you’re telling me if I just buy more stuff I get a discount?

Wow.

Who knew capitalism worked like this?

And the best part? You don’t even have to be smart about it. Just order 10,000 units of something and boom-savings.

Meanwhile, I’m over here trying to figure out why my last 500 vials of lidocaine disappeared and now my patients are crying because they can’t get numbing shots.

Maybe if I stopped trusting the system and started trusting my spreadsheet I’d be fine.

Or maybe I should just open a Patreon.

Thanks for the advice, I guess.

Aki Jones

November 29, 2025 AT 16:35Have you considered that this entire system is a psychological manipulation tactic designed to make providers feel empowered while remaining financially trapped?

They give you the illusion of control-‘shop around!’ ‘track your inventory!’ ‘use secondary distributors!’-but the real power lies with the three conglomerates that control every single manufacturer, every PBM, every warehouse.

They allow you to ‘save’ 20%... so you’ll keep buying from them.

They want you to believe you’re clever for finding short-dated stock.

But what happens when the next shortage hits? Who gets priority? The clinic that ordered 10,000 units? Or the hospital that has a contract with Cardinal Health?

And why is it that every time someone tries to expose this, they get blacklisted from supplier lists?

This isn’t procurement-it’s a controlled demolition of autonomy, wrapped in bullet points and Excel sheets.

Wake up.

Shirou Spade

November 29, 2025 AT 20:10There’s a deeper truth here: we treat medicine like a commodity because we’ve forgotten it’s a human necessity.

When we optimize for cost per unit, we reduce suffering to a spreadsheet cell.

It’s not wrong to save money-but when saving becomes the only metric, we lose sight of why we’re doing this.

Is a 25% discount worth the anxiety of wondering if your next batch will expire before your next patient walks in?

Is a PBM rebate worth the silence of a patient who can’t afford the co-pay even after the ‘discount’?

Maybe the real question isn’t how to buy cheaper-but how to build a system where no one has to choose between affordability and survival.

Until then, we’re just rearranging deck chairs on a sinking ship.

Erika Hunt

December 1, 2025 AT 08:30I’ve been doing this for 12 years, and honestly, the biggest win wasn’t the discount-it was the peace of mind.

Before I started tracking expirations, I’d wake up in a cold sweat wondering if I had enough lidocaine for the next week.

Now? I have a Google Sheet with color-coded rows. Green = good. Yellow = 30 days out. Red = order now.

It’s not glamorous. It’s not sexy. But it’s the difference between panic and routine.

And yeah, the savings are real-like, enough to hire a part-time nurse.

But the real gift? Not having to feel like I’m gambling with people’s health every time I place an order.

Just do the work. It’s worth it.

Josh Zubkoff

December 1, 2025 AT 16:29Let’s be real: this whole post is just a glorified LinkedIn post written by a pharmaceutical consultant trying to sell a $5000 ‘Bulk Procurement Mastery’ course.

Everyone’s acting like this is some groundbreaking revelation, but every clinic in America with more than three employees has been doing this since 2017.

And yet-still, somehow-we’re all still paying too much.

Why? Because the system is designed to keep you confused.

They want you to think it’s about ‘inventory management’ or ‘secondary distributors’ or ‘short-dated stock’.

It’s not.

It’s about who owns the supply chain.

And they’re not letting go.

So go ahead. Buy your 10,000 units of metformin.

It won’t change a thing.