Bleeding Risk Calculator for Bone Marrow Disorders

This tool helps estimate bleeding risk based on platelet count and coagulation factors. Input your platelet count and coagulation values to assess risk level and receive appropriate management recommendations.

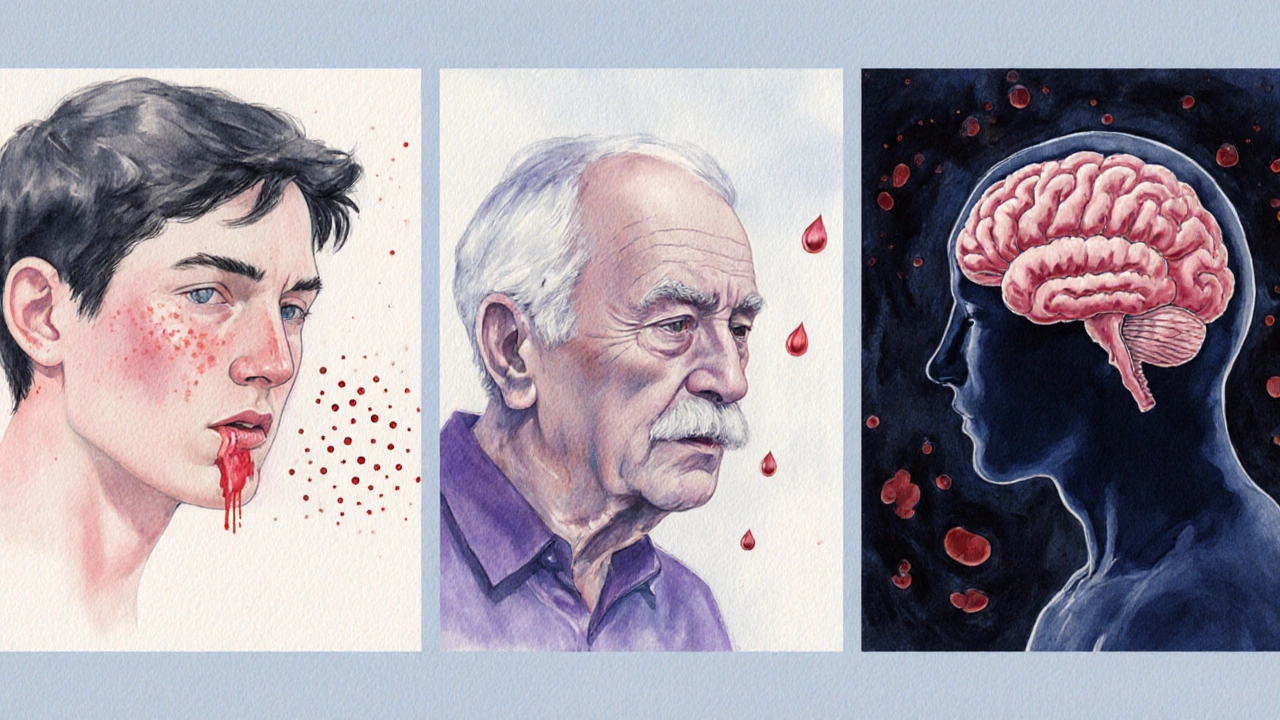

When the marrow that makes blood cells goes haywire, the body’s ability to stop bleeding can crumble. This article unpacks which bone marrow disorders tip the scales toward dangerous hemorrhage, why they do it, and what patients and clinicians can do to stay safe.

Key Takeaways

- Low platelet production is the primary driver of bleeding in most marrow diseases.

- Aplastic anemia, myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) and acute leukemias carry the highest hemorrhagic risk.

- Routine labs (CBC, PT/INR, aPTT) plus clinical scoring (ISTH‑BAT) guide early detection.

- Transfusion thresholds, antifibrinolytics, and targeted therapies can dramatically cut bleed rates.

- Prompt evaluation of any new bruising, petechiae, or mucosal bleeding is essential.

Bone Marrow Disorders are a group of hematologic conditions in which the marrow’s ability to produce healthy blood cells is impaired. The spectrum includes aplastic anemia, myelodysplastic syndromes, acute leukemias, and marrow infiltrative diseases such as lymphoma or myelofibrosis.

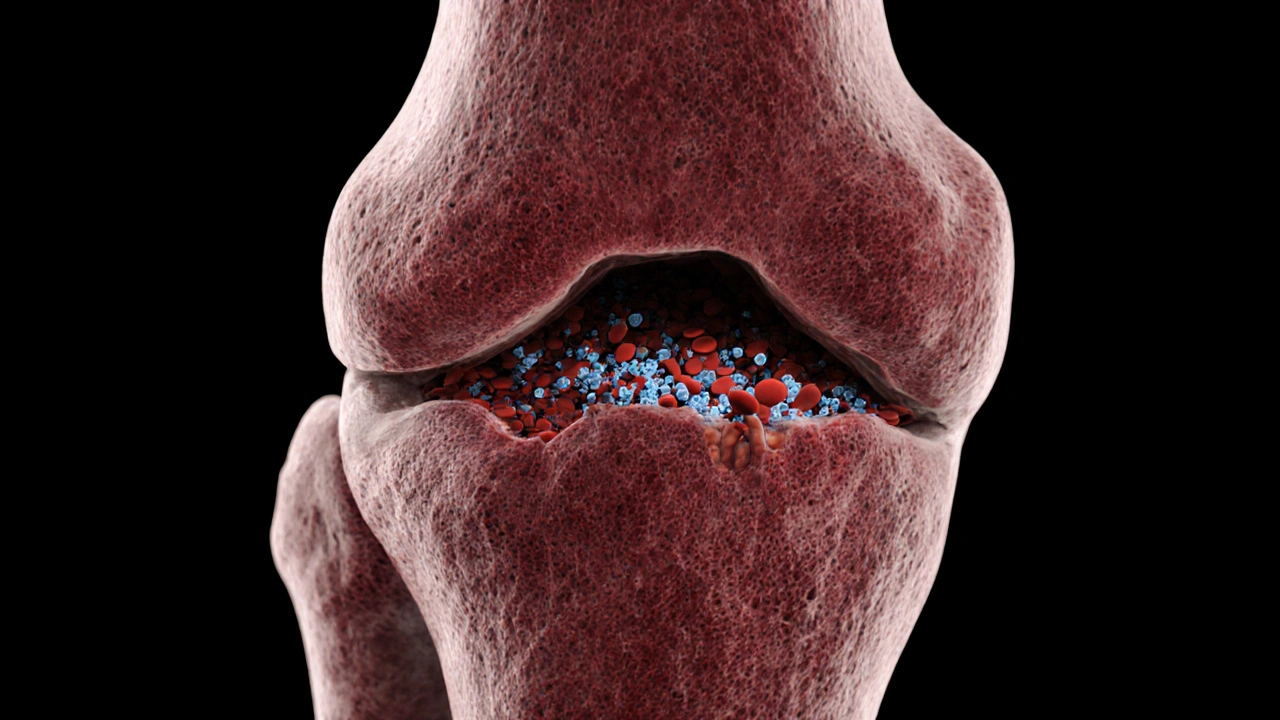

Why Bleeding Happens: The Hematologic Link

Every bleeding episode can be traced back to a shortage or dysfunction of one of three key components:

- Platelets - tiny cell fragments that plug vascular cracks.

- Coagulation factors - proteins that form a fibrin mesh.

- Vascular integrity - the lining of blood vessels.

Bone marrow disorders primarily cripple the first two. When platelet count drops below 20×10⁹/L, spontaneous mucosal bleeding becomes common; below 10×10⁹/L, life‑threatening intracranial hemorrhage can occur.

Disorders With the Highest Bleeding Risk

Not all marrow diseases are created equal. Below is a quick snapshot of the most notorious culprits.

| Disorder | Typical Platelet Range (×10⁹/L) | Coagulation Abnormalities | Common Bleeding Manifestations | Key Management Tips |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aplastic Anemia | 5-30 | Normal PT/INR, occasional low fibrinogen | Petechiae, gum bleeding, GI bleed | Transfusion support, immunosuppression, consider HSCT |

| Myelodysplastic Syndromes (MDS) | 10-50 (often fluctuating) | d>Elevated PT/INR in advanced diseaseEpistaxis, menorrhagia, intramuscular hematoma | Growth factors (eltrombopag), lenalidomide, transfusions | |

| Acute Leukemia | Variable; often <20 during induction | Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) common in AML M3 | Purpura, CNS bleed, severe mucosal hemorrhage | Prompt cytoreduction, DIC protocol, platelet prophylaxis |

| Myelofibrosis | 20-100 (often high‑molecular‑weight platelets) | Acquired vonWillbrand‑type factor deficiency | Splenic rupture, GI bleed | JAK‑inhibitors, splenectomy, factor replacement |

| Lymphoma Infiltrating Marrow | 30-80 (may be normal) | Coagulopathy from tumor‑associated cytokines | Deep tissue hematoma, postoperative bleed | Chemo‑induced remission, prophylactic anticoagulation judiciously |

How Clinicians Evaluate Bleeding Risk

Assessment starts with a simple complete blood count (CBC). Look for:

- Platelet count<20×10⁹/L - high‑risk zone.

- Hemoglobin<8g/dL - suggests ongoing blood loss.

- White‑blood‑cell differential - blasts indicate leukemia‑related DIC.

Coagulation labs (PT/INR, aPTT, fibrinogen, D‑dimer) help spot factor deficiencies or DIC. The International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis Bleeding Assessment Tool (ISTH‑BAT) quantifies clinical severity by scoring bruises, petechiae, nosebleeds, gum bleeds, gastrointestinal and intracranial events.

Proactive Management Strategies

Once a patient’s risk profile is clear, the care plan usually blends four pillars:

- Transfusion thresholds - maintain platelets≥10×10⁹/L for non‑critical patients,≥50×10⁹/L for invasive procedures or active bleeding.

- Pharmacologic support -

- Thrombopoietin receptor agonists (eltrombopag, romiplostim) raise platelet production in MDS and aplastic anemia.

- Antifibrinolytics (tranexamic acid) curb mucosal bleeding, especially in leukemia‑related coagulopathy.

- Factor concentrates or fresh‑frozen plasma correct specific deficiencies (e.g., acquired vonWillbrand disease in myelofibrosis).

- Targeted disease therapy - disease‑modifying agents (azacitidine for high‑risk MDS, all‑trans retinoic acid for APL) shrink the malignant clone, indirectly normalizing counts.

- Bone‑marrow transplant (HSCT) - the only curative option for severe aplastic anemia or refractory AML, but it carries its own bleeding risks during conditioning.

Preventive Measures Patients Can Take

Even with medical supervision, everyday habits matter:

- Avoid high‑impact sports or contact activities when platelets are below 30×10⁹/L.

- Use a soft toothbrush and avoid aspirin or NSAIDs unless prescribed.

- Keep gums healthy; untreated dental disease can trigger bleeds.

- Carry a medical alert card that lists the specific marrow disorder and current platelet threshold.

- Schedule regular CBCs; trending platelets often predicts an upcoming bleed before symptoms appear.

When to Seek Immediate Care

Bleeding can turn critical in minutes. Call emergency services if you notice:

- Sudden, severe headache or neurological changes - possible intracranial bleed.

- Vomiting blood or black, tarry stools - gastrointestinal hemorrhage.

- Rapidly expanding bruises, especially in the abdomen or thigh.

- Uncontrolled nosebleeds lasting more than 20minutes despite pressure.

- Severe gum bleeding that doesn’t stop after applying gauze.

Future Directions: Emerging Therapies

Research is hot on two fronts: gene‑editing approaches (CRISPR‑Cas9) aiming to correct inherited marrow failure genes, and novel small‑molecule inhibitors that selectively boost megakaryocyte maturation without fueling malignant clones. Early‑phase trials report platelet gains of 30‑50% within weeks, hinting at a future where transfusion dependence could become rare.

Frequently Asked Questions

What platelet level is considered safe for minor surgery?

Guidelines generally recommend a platelet count of at least 50×10⁹/L for minor procedures (e.g., dental extraction). For more invasive surgeries, 100×10⁹/L is the target.

Can I take vitaminK supplements to improve clotting?

VitaminK helps with certain clotting factors, but most marrow‑related bleeding stems from platelet deficiency, not factor deficiency. It’s best to discuss any supplement with your hematologist.

How often should I get a CBC if I have MDS?

For low‑risk MDS, a CBC every 1-2months is typical. High‑risk or transfusion‑dependent patients may need weekly monitoring during treatment cycles.

Is tranexamic acid safe for long‑term use?

Short‑term use during active bleeding is well‑studied and safe. Chronic use raises concerns about thrombosis, so clinicians limit it to acute episodes unless a specialist advises otherwise.

What lifestyle changes help reduce bleeding risk?

Avoid alcohol excess, maintain good oral hygiene, steer clear of contact sports when platelets are low, and always wear protective gear if you’re at risk of falls.

Understanding the link between bone marrow dysfunction and bleeding equips patients and providers to act early, treat aggressively, and, when possible, prevent catastrophic hemorrhage.

Heather Jackson

October 14, 2025 AT 13:33OMG this is sooo intense!!!

Akshay Pure

October 17, 2025 AT 18:53When one surveys the corpus of marrow‑derived cytopenias, the epistemic hierarchy becomes unmistakably apparent. Aplastic anemia, for instance, epitomizes a pristine defect in hematopoietic stem‑cell viability, whereas myelodysplastic syndromes represent a kaleidoscopic spectrum of clonal dysplasia. The author’s calculator, while eminently utilitarian, glosses over the nuanced interdependence of platelet biogenesis and coagulation factor synthesis. One must also contemplate the stochastic nature of leukemic infiltration, which precipitates abrupt thrombocytopenia beyond mere numerical thresholds. Ultimately, the clinical gestalt supersedes algorithmic determinism.

Steven Macy

October 21, 2025 AT 00:13At its core, the relationship between marrow failure and bleeding is a reminder of how fragile our hemostatic balance truly is. Low platelet output is the most immediate culprit, yet the coagulation cascade can be equally deranged in advanced disease. The article captures the essentials, but clinicians should also weigh patient‑specific factors like concurrent medications. Vigilance for subtle signs-petechiae, gum bleeding-can avert catastrophic events. A measured, patient‑centered approach remains paramount.

Matt Stone

October 24, 2025 AT 05:33Platelet count under 10 is life‑threatening. Need transfusion now.

Joy Luca

October 27, 2025 AT 09:53From a hemostasis standpoint, thrombopoietic insufficiency translates to a quantitative deficit in primary plug formation, while concomitant PT/INR elevation signals secondary wave dysfunction. The synergistic effect amplifies hemorrhagic propensity, especially in mucocutaneous beds. Empiric support with platelet concentrates, coupled with fibrinogen replacement when indicated, aligns with best‑practice guidelines. Moreover, antifibrinolytic agents such as tranexamic acid can shore up clot stability in refractory cases. Integrating these modalities into a tiered protocol optimizes patient outcomes.

Jessica Martins

October 30, 2025 AT 15:13The risk calculator offers a concise overview of platelet thresholds and INR implications. It correctly emphasizes immediate medical evaluation for high‑risk values. However, clinicians should still corroborate findings with a comprehensive clinical assessment.

Doug Farley

November 2, 2025 AT 20:33Wow, another shiny widget that pretends to replace a real doctor. Sure, because a button is all you need to stop an intracranial bleed.

Scott Davis

November 6, 2025 AT 01:53I get the sarcasm, Doug, but the calculator does at least flag critical thresholds that many might overlook.

Calvin Smith

November 9, 2025 AT 07:13Honestly, if you’re still counting platelets on a piece of paper, this tool is a miracle. It even tells you when to panic and when to chill. Brilliant, right?

Alex Feseto

November 12, 2025 AT 12:33The exposition could benefit from a more rigorous citation of contemporary hematological guidelines. In particular, the thresholds for platelet transfusion warrant explicit reference to the British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Such scholarly precision would enhance the article’s academic standing.

vedant menghare

November 15, 2025 AT 17:53Namaste friends! I appreciate the effort to demystify bleeding risks, especially for patients in remote regions. Including cultural considerations, such as dietary influences on vitamin K, could make the tool even more inclusive. Keep up the good work.

Kevin Cahuana

November 18, 2025 AT 23:13Great resource! If you’re ever in doubt, remember that bedside assessment and a quick conversation with your hematologist can save lives. Stay calm, follow the thresholds, and don’t hesitate to call for help.

Danielle Ryan

November 22, 2025 AT 04:33They don’t tell you this, but the real danger is the hidden nanotech in the blood that the government uses to control us!!! The calculator is just a distraction, a smokescreen!!!

Robyn Chowdhury

November 25, 2025 AT 09:53Well, that was… educational 🤔. The article covers the basics, but could use a sprinkle of philosophical depth. 🙄

Deb Kovach

November 28, 2025 AT 15:13✅ Helpful summary! ✅ The bleed risk stratification aligns with current NCCN recommendations. ✅ Remember to reassess labs after any transfusion.

Sarah Pearce

December 1, 2025 AT 20:33Hmmmmm… the article??… could be better…,, like maybe add more graphs,,,??!!

Ajay Kumar

December 5, 2025 AT 01:53Thanks for the clear layout! I’ve seen patients with MDS where platelet counts swing wildly, so having a quick reference is gold. Also, don’t forget to check for concurrent liver dysfunction, as that can further impair coagulation. Stay safe out there.

Sandy Gold

December 8, 2025 AT 07:13Sure, the tool is useful, but let’s not forget that many of these thresholds are based on outdated trials. Modern real‑world data suggest we can be a bit more lenient with platelet transfusions in low‑risk settings. Just saying.

Jackie Berry

December 11, 2025 AT 12:33Reading through this piece reminded me of the first time I encountered a patient with acute leukemia who presented with spontaneous epistaxis. The urgency was palpable, and the medical team had to act within minutes to stabilize the situation. We initiated platelet transfusions while simultaneously ordering a full coagulation panel. The results showed a mildly elevated PT/INR, which prompted the addition of fresh frozen plasma to the regimen. Throughout the process, the nursing staff vigilantly monitored for any signs of intracranial hemorrhage, a dreaded complication in such severe thrombocytopenia. Our interdisciplinary approach, involving hematology, neurology, and critical care, exemplified the importance of rapid, coordinated action. Moreover, we educated the patient’s family about the risks and the necessity of close observation. This experience reinforced the article’s emphasis on proactive risk assessment. It also highlighted that while calculators are invaluable, they cannot replace clinical intuition and real‑time judgement. In another case, a patient with myelodysplastic syndrome was on an eltrombopag trial, which modestly improved platelet counts but did not fully eliminate bleeding episodes. Here, personalized medicine played a crucial role, tailoring therapy to the individual’s response. The case underscored that management strategies must be adaptable, considering both laboratory values and patient‑specific factors. Additionally, anticoagulant use in patients with concurrent atrial fibrillation posed a therapeutic dilemma, requiring careful balancing of thrombotic versus hemorrhagic risks. The article’s mention of avoiding anticoagulants in low platelet scenarios aligns with these clinical decisions. Finally, the psychological impact on patients dealing with constant bleeding anxiety cannot be overstated; comprehensive care must address mental health alongside physical health. In conclusion, the risk calculator is a solid foundation, yet its true power emerges when integrated with vigilant bedside assessment, multidisciplinary collaboration, and compassionate patient communication.